René Roselle, Ph.D., Director of Teacher Preparation, Farrington College of Education, Sacred Heart University, Fairfield, CT, roseller@sacredheart.edu

Sarah Tropp-Pacelli, Director of Education and Strategy, Sacred Heart University’s Discovery Science Center and Planetarium, Bridgeport, CT, stropppacelli@shudiscovery.org

With the recent stress and demands placed on public schools as a result of the pandemic, an opportunity has emerged for Educator Preparation Programs to reimagine and redefine clinical experiences to include museums. Museums have become educational environments (Dilmac, 2016), so they might also become community-based assets for preparing teachers. Constructivist learning theory has become deeply embedded in the educational experiences that museums are providing. No longer are they places where one passively observes, moving from exhibit to exhibit. Interactive and simulation-based experiences have become increasingly more popular, and they require a sophisticated level of instruction from planning to execution. The rigor of this learning environment affords teacher candidates a rich and inspiring and life-giving clinical experience. Also, because museums are open to the public, they are places where children and adolescents of various backgrounds can access information and knowledge, providing teacher candidates with expansive teaching experiences with diverse student populations.

Last semester, Sacred Heart University in Fairfield, Connecticut, placed nine undergraduate teacher candidates at the local Discovery Science Center and Planetarium so they could fulfill a 30-hour clinical practice requirement. Sarah Tropp-Pacelli, the center’s director of education and strategy, recognized that this was the first time most of these teacher candidates may have tried to teach. Taking that into consideration, she required each candidate to prepare a 10-minute mini-lesson on the topic of their choice. The candidates were divided into three groups, each one overseen by a staff educator at the center. Candidates presented their mini-lessons and then helped one another brainstorm how to digitize their lessons to a digital format, as all the instruction would need to be virtual for school year 2020–21. The center’s education staff spent up to six weeks training each candidate. Each required training included a 1.5-hour professional development session in which the candidates presented their mini-lessons and observed their peers in action. Candidates were offered weekly opportunities to shadow teach and were provided with written tips for improving certain aspects of their teaching, such as asking questions, modeling activities, and pacing. They also taught a variety of lessons aligned with Next Generation Science Standards. Ms. Tropp-Pacelli said, “I believe this plan will provide them with the training they need as well as the experience to feel comfortable engaging with one another more. We will continue to adjust as we go, and I expect that following this plan will lead to them all being exemplary STEAM teachers by the end of this semester.”

Teacher education is changing, and teacher preparation must be prepared to change with it. Our reliance on public schools as sole singular partners in the work of educating future teachers may need to broaden out to include community-based partners, such as museums. “A culture that takes this mission lightly by delegating it solely to its schools is not wise” (Goodlad et al., 2004, p. 5). The pandemic has pushed us to see and do things differently, and that may be a silver lining!

Video: Professional Development Museums (PDMs)

Figure 1: A High School Student “Engineers” a Paper Airplane

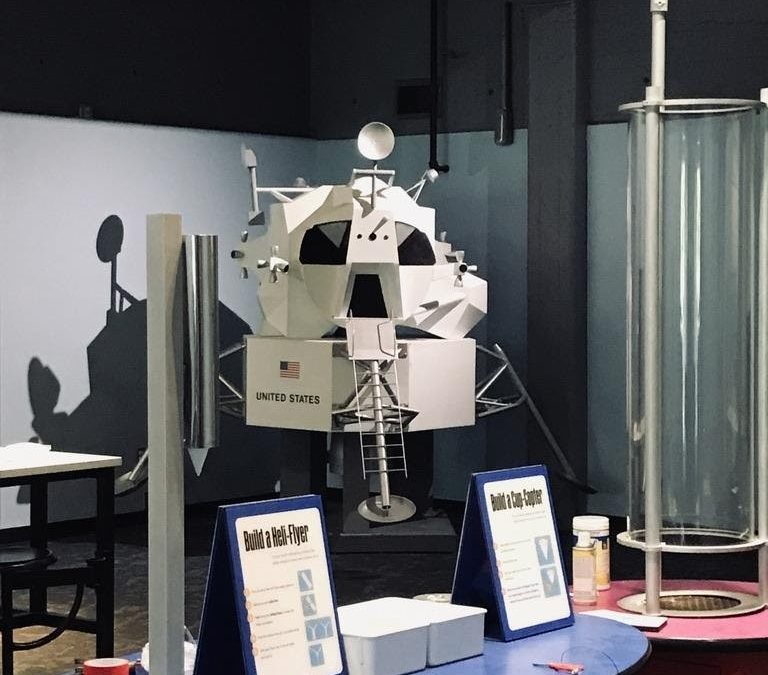

Figure 2: Space Simulation Experiences Are Offered to K-12 Students

References

Dilmac, O. (2016). The effect of active learning techniques on class teacher candidates’ success rates and attitudes toward their museum theory and application unit in their visual arts course. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 16(5), pp. 1587–1618.

Goodlad, J. I., Mantle-Bromley, C., & Goodlad, S. J. (2004). Education for everyone: Agenda for education in a democracy. Jossey-Bass.